The sad and glorious history of Washington's 'F' pit - delving into the dramatic past of a place that deserves our respect

and live on Freeview channel 276

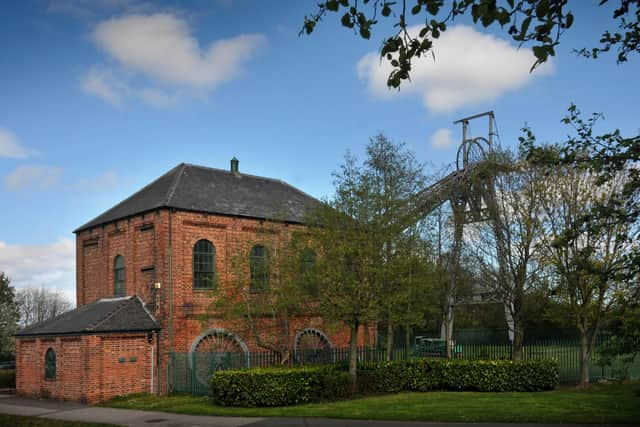

The best we can manage is to visit somewhere like the ‘F’ Pit Museum in Washington (when we are able to), then imagine. But located in a quiet corner of Albany, the calmness of the place belies a dramatic history.

At its peak the pit produced almost half-a-million tons of coal a year. It also claimed the lives of many workers – although the exact figure will never be known – and it’s impossible to do better than estimate how many died from illnesses contracted there.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCoal mining was at the heart of the Industrial Revolution and crucial to more than one war effort. So pay attention. It deserves our respect. Here’s the story of Washington’s ‘F’ pit.

In the beginning...

In December 1775 the coal that lay beneath Washington was leased to William Russell, a banking and mining tycoon from Sunderland and a Georgian equivalent to today’s billionaires. He later bought Brancepeth Castle.

The leasers were three Lords of the Manor of Washington, including Robert Shafto, a public schoolboy immortalised by the song Bobby Shafto’s Gone To Sea; although the maritime advantages of wearing silver buckles on his knee remain a mystery to historians.

A series of pits were sunk in the leased area, known as “the royalty”, they would comprise New Washington Colliery. With nothing owed to imagination, they were named alphabetically from ‘A’ to ‘I’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe first extracted coal was taken from the colliery in March 1778 and transported to Sunderland by waggonway; a horse-drawn railway. By 1786 another waggonway ran to the Tyne, meaning Washington coal could be exported by ships on both Wear and Tyne.

The ‘F’ pit shaft was sunk around 1777, but abandoned in 1786 after an explosion left it flooded; a reminder of the perennial dangers of mining. After some debate as to whether it should be filled and replaced by another shaft, it eventually reopened in 1820.

In 1856 it was deepened to reach the Hutton seam (the seams had more interesting names than the shafts) to 660 feet, about 200 metres. Readers of a nervous or claustrophobic disposition might not wish to dwell upon this. ‘F’ was now the most productive of Washington Colliery’s nine pits.

Heyday and decline

Some new buildings would be occasionally constructed until the 1950s, but the last significant remodelling of the colliery surface came in 1903.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBetween 1926 and 1927 the new 929 feet ‘J’ pit was sunk to reach the Busty seam. As mentioned, the seams had more interesting names than the pits and this one still manages to amuse schoolboys of all ages.

Also in 1927 came a also big moment for Washington’s miners when new owners modernised the colliery, introducing electricity and pneumatic picks. It still wasn’t a fun job, just a bit more tolerable.

An even bigger moment came on January 1, 1947 when Clement Attlee’s Labour government nationalised the coal mining industry. The colliery was no longer owned privately, but by the newly formed National Coal Board (NCB).

In 1954 the shaft at ‘F’ Pit was deepened to also reach the Busty seam (stop it). By the mid-1960s it was annually producing 486,000 tons of saleable coal and had a workforce of over 1,500. But it was to be the pit’s last hurrah. Coal mining no longer provided a job for life.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe NCB had a programme of modernisation which Washington would not be part of. All of its remaining pits including ‘F’ closed on Friday, June 21, 1968.

Following closure the NCB presented the pit’s winding house (the building containing the huge coil of steel rope that raised and lowered the lift) and headgear to the people of Washington to honour their mining heritage.

Nearby Springwell Colliery had gone in 1965, Harraton in 1932. When Usworth followed in 1974 it was the end of Washington coal mining forever.

Grim statistics

Around 150 people are known to have died at Washington Colliery, although the exact number is impossible to know as records were not scrupulously kept 200+ years ago.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe biggest single loss of life came on August 9, 1851 when 34 men were killed by an explosion caused by a lighted candle.

An 1828 explosion took 12 lives. The youngest victim was seven year-old Thomas Carter. Four other victims were under 12. The colliery’s final fatality was that of William Longworth, 31, on August 25, 1957.

Neighbouring Usworth Colliery claimed at least 238 lives, Harraton 139 and Springwell 106.

Mining became progressively safer. But it was never easy and how much former miners miss their work is a question that only former miners can fully answer.

Preserved for history

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Washington ‘F’ pit museum was opened in 1976 by the Washington Development Corporation. In April 2013 Sunderland City Council took over the Grade II-listed building.

The last visible remnant of ‘F’ pit is the museum which stands today. Visitors can see the steam engine used to wind the lift up and down. It was once steam operated, but now works from an electric motor for demonstration purposes.

In the 1970s the Washington Development Corporation took up restoration of the steam engine. It’s recognised as a unique example of 19th century mining machinery: a twin-cylinder horizontal type Simplex for one of the earliest colliery shafts in England.

And if there’s anything that engineering buffs love, it’s a twin-cylinder horizontal-type Simplex steam engine.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor those of us who can barely distinguish between a twin-cylinder horizontal type Simplex and a tumble dryer, the best we can do is to pop along to the ‘F’ pit (again, when we are able to), then imagine dropping down into the blackness to carry out one of the toughest and most dangerous jobs that civilians have ever performed.