Thousands of UK lives lost and it all started in Sunderland

Local historian Beverley Taylor has been looking back to the start of the epidemic of the 1830s.

“In October 1831, there seemed nothing unusual when a ship carrying sailors from the Baltic states docked in Sunderland,” said Beverley.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut little did the people of the town know, it was the arrival of cholera morbus for the very first time.

Doctors were aware of what cholera did to the human body, but they didn’t know how to prevent its spread.

“Theories stated that it was transmitted by touch or carried by bad smells. Orders were issued for houses to be lime-washed and barrels of tar and vinegar were burned in the streets to eliminate the miasma.

“Of course, these attempts to hold the disease at bay failed.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe symptoms of cholera were horrific and included profuse diarrhoea, vomiting and sweating. Death would often occur within hours of the first symptoms.

Doctors recommended that the patient’s fluid intake should be restricted but today’s medical knowledge shows the opposite is true. The disease is fatal if water and salts lost by the body are not replaced.

“The fact remains that cholera is only a deadly disease if it is not treated correctly,” said Beverley.

She added: “It is likely the first Sunderland victim was a River Pilot, Robert Henry, but his death went unreported. On October 17, Isabella Hazard, 12, from Sunderland quayside, fell ill and died within 24 hours.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA week later, Keelman Willliam Sproat, 60, also contracted the disease.

“Dr William Reid Clanny and Dr James Butler Kell managed to keep him alive for three days, but he finally succumbed to the disease, with his son and granddaughter, as well as the nurse who handled his body, also being struck down by the dreadful disease.”

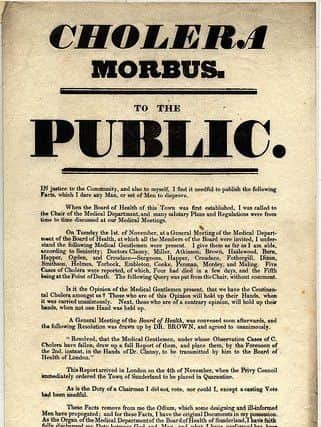

“Nationally, the Central Board of Health met daily from June 1831 until May 1832,” Beverley said.

“It offered advice and issued information leaflets to parochial Vestry Committees who were responsible for taking precautions within their own parishes.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA ruling was made that all ships arriving from the Baltic were to be put under strict quarantine, spending ten days in port. Only after a doctor had given those on board the all clear were they free to step onto dry land.

By the end of November 1831, all vessels arriving around Britain from Sunderland were also quarantined.

These measures were not entirely effective, as the first death ashore in London was John James, a ship scraper who had been off the ship Elizabeth from Sunderland for just two days. He died on February 11, 1832.

In Sunderland in June 1831 the Board of Health was set up with Dr Clanny, Senior Physician at the Sunderland Infirmary, at the helm of the Medical Department.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnother key figure was James Butler Kell, an army doctor with experience of suppressing an outbreak of cholera while stationed in Mauritius. The Board drew up a Code of Sanitation, which looked at standards of housing, sewage and water supply.

“On November 1, the outbreak was officially declared. Kell put his own barracks – home of the 82nd regiment – into strict quarantine as it was right in the heart of the cholera district.

Not a single man took ill, but for the rest of the town the disease spread rapidly.”

The town’s cemeteries struggled to cope with the rising death toll, forcing a new cholera burial ground to be opened in Hind Street. The rate at which the deaths occurred coupled with the fear of the spread of disease, meant that this became a mass shared grave.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1988, during work on a new ring road, the remains were removed and reinterred in Bishopwearmouth Cemetery.

Doctors Clanny and Kell arranged a clean-up of the streets of Sunderland, providing men to sweep the streets twice daily and giving free quicklime and they provided blankets for the poor.

Thankfully towards the end of December 1831, the disease began to decline in Sunderland, however, it had already spread across Britain where around 52,000 lives were claimed throughout the outbreak.

Beverley said: “On January 9, 1832, the Board of Health declared that Sunderland was free from the disease.”

“But sadly up to that point 215 deaths had been reported in the town.”