The grimness of life in a Sunderland Victorian workhouse

Norman Kirtlan, an esteemed historian from the area, will be sharing his talk, which is called To the Workhouse Born.

So if you want to learn why donkeys, snails and gas works all played a part in Sunderland’s past health care, get along.

In the meantime, Chris Cordner finds out more:

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIf a child was lucky enough to survive beyond infancy, then there were still plenty of diseases just waiting to claim their lives.

Just as interesting, there were plenty of strange cures to ward them off.

One of the strangest however, involves a humble beast that featured in every childhood trip to Roker and Seaburn – the donkey.

At the end of the summer season, Victorian donkey owners often hired out their animals to earn a few pounds.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut the most lucrative return wasn’t the beaches of Wearside – it was the tradition of the annual whooping cough run.

It happened every year, at the beginning of Autumn.

The donkeys would be led around the streets of the town to be greeted by queues of anxious mothers clutching equally nervous toddlers in their arms.

After handing over a silver threepenny bit, the ladies would then pass each child nine times around the donkey’s girth, before heading home.

They would be safe in the knowledge that if little Johnnie didn’t have whooping cough, then he was certainly protected from getting it in the future.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNo one knows for sure where this custom originated from. But the donkey was always held in high esteem because of its association with Christ.

And, regardless of any logical reason for assuming that one’s child would indeed be protected from the dangers of whooping cough, the custom carried on until the early 19th century.

Another creature that featured in the cure of childhood diseases was the long-suffering snail.

Tuberculosis was supposed to be cured by eating a live snail, and if your kids had dreaded warts on their fingers, then it was a simple matter of throwing the unshelled mollusc at a thorn bush. If the poor creature stuck, then your warts were history.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAny serious and life-threatening illness could be treated by eating a live mouse. The fact that such rodents probably carried more disease than the bairn had to start with was often lost on the Victorian mother.

Rose water was often used to treat headaches, and for childhood deafness.

Walter Ettrick – a rich and slightly eccentric 18th century landowner who gave his name to Ettrick Grove – advocated the use of a garden cabbage.

All the sufferer’s mother had to do was trim the stalk into a conveniently shaped point, insert this into the bairn’s afflicted ear and hold it there for two days.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

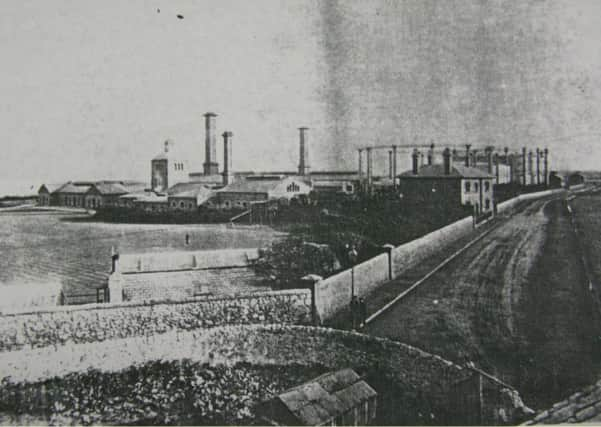

Hide AdHendon residents had their very own cure for common cold, and that involved the local gas works.

Dragging the bairn along to the limestone wall that surrounded the gasworks, the little one would be held up to inhale the fumes from the coal gas for half an hour or so.

If this didn’t work, then a workman guarding a hot, bubbling barrel of tar would be sought. A ha’penny in the workman’s pocket would ensure unfettered access to this cure-all remedy.

Tar barrels were probably the longest surviving local remedy, their use not dying out until the 1920s.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThankfully for modern parents, helpful family doctors and the local chemist are all on hand to prescribe remedies that don’t involve wriggling molluscs, indignant donkeys or trips to the gasworks.

To the Workhouse Born is the title of the talk, to be given by historian Norman Kirtlan, on Tuesday, April 19, at 7.30pm in Saint George’s Church Hall, Grange Crescent.

Admission £1 for SAS members and £2 for guests.