What you might not know about the history of Washington Village - it's not as sleepy as you thought

and live on Freeview channel 276

You probably know about Washington Old Hall; perhaps also the medieval doorway, Gertrude Bell living nearby or even the tragic tale of the drowned “witch” Jane Atkinson. But that’s only part of it.

Our first story was popularised by headmaster and Washington stalwart Fred Hill in a book he wrote in the 1940s. Its authenticity is disputed, but the tale is undiminished.

Stand and deliver

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne evening in 1770, or so the story goes, a posh lady called Margaret Banson was travelling home in her carriage when her driver was stopped at pistol point by a highwayman.

The robber made off with half a guinea. He later relieved a postman of his bags.

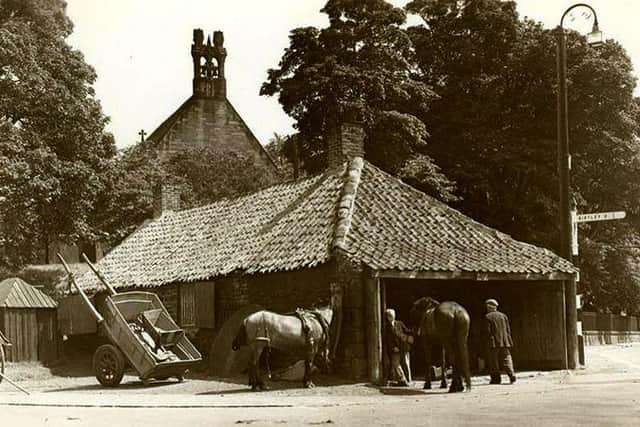

Regrettably for our highwayman, he had been spotted holding up Mrs Banson by a small boy who recognised the thief’s grey mare from Washington Village’s blacksmiths (now the Forge restaurant).

The little lad grassed him up good and proper. Law enforcers of the time went to see the blacksmith, Bill Allison, who confirmed that he tended to a horse of that description every Friday.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe lawmen lay in wait the following Friday and the highwayman, Robert Hazlitt, who had held down a respectable position as a clerk before turning to crime, was duly nicked.

His cries of innocence were undermined a tad by when his bags were searched and a pistol and black mask discovered. As circumstantial evidence goes, he may as well have written “Swag” on his bag and had the set.

Hazlitt confessed and told his captors where the loot was, hoping for a bit of compassion in court. But his luck ran out further when he was tried at Durham Assizes.

Perhaps he considered the judge, Sir John Fielding, to be prejudiced; although in fairness there is nothing more likely to steer a judge away from leniency than recognising the bloke in the dock as the same scoundrel who had robbed him a few months earlier.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRobert Hazlitt was hanged and gibbeted on Tuesday, September 18, 1770. Inevitably, his ghost is said to lurk around the village. Please let the Echo know if you see the ghost as we would like an interview.

Cyril Lomax – incredible war artist

The artist Canon Cyril Lomax was born in 1871 in Cheshire and educated at Oxford. He came to Washington’s Holy Trinity Church in 1897 becoming rector between 1899 and 1946.

In 1900, he also became chaplain to a battalion of the Durham Light Infantry. In July 1916 he joined the battalion in France at the peak of World War One. Lomax would become renowned for the illustrations in his letters.

The National Trust said: “Cyril, who was an accomplished artist and prolific letter writer, saw the devastation during the Battle of the Somme and described the reality of life in the trenches.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCanon Lomax’s powerful letters and sketches are so important that some are kept by the Imperial War Museum, although they were displayed in Washington Old Hall in 2016; the centenary of the Somme.

Lomax did much to save the hall from demolition in the 1930s. He died in 1947.

Washington child labour tragedy that helped to change UK law

The Chimney Sweepers Act 1840 made it illegal for anyone below the age of 21 to be a chimney sweep. It was widely ignored.

So on September 28, 1872 chimney sweep Thomas Clark turned up at Washington New Hall to clear the flues. The hall, later Dame Margaret Hall, was owned by Liberal MP Isaac Bell, grandfather of Gertrude Bell.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdToo big to reach a particular blockage, Clark sent up his six, yes, six year-old assistant Christopher Drummond. After 15 minutes Christopher was still up the chimney and silent.

Another boy was sent up to free Christopher who was gasping for air and eventually dragged out by a rope wrapped around his legs. An attempt to revive him in the Cross Keys public house, which still trades close by, was unsuccessful.

The following year Clark was given six months hard labour after his conviction for manslaughter. The horrific incident led in part to the Chimney Sweepers Act 1875. This time the law was properly enforced and the barbaric practice of sending children up chimneys was finally consigned to history.

Some good came out of this horrendous tale then, although how much consolation this gave to the family and friends of little Christopher Drummond we can only guess.

Job Atkinson – the no-nonsense beadle of Washington.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn the early years of the 19th Century the village didn’t have a policeman as such. Durham Constabulary was not formed until 1839.

But Washington had someone who was as effective as any police officer; Job Atkinson the parish beadle. A beadle was an official of the church and a sort of sheriff. Job took his civic duties very seriously. Indeed, it seems he took most things very seriously. Not one of life’s gigglers.

He must have been a sturdy sort of chap. He would lock up drunks and other such reprobates in the vault behind the medieval doorway (to the left as you leave the Washington Arms and regrettably bricked up in 1947).

Job would also put scallywags into the stocks, situated between the Holy Trinity Church and the blacksmiths shop, for a good pelting with anything rancid that came to the hands of the village’s most outraged inhabitants.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSuch methods of justice are of course long gone, although not everyone regards this as progress.

Stocks, highwaymen (perhaps), child tragedy, war artists, witch trials (unlikely, but a great story), mysterious doorways, Gertrude Bell… Anywhere as idyllic as Washington Village appears to be often turns out to have a pulsating past.