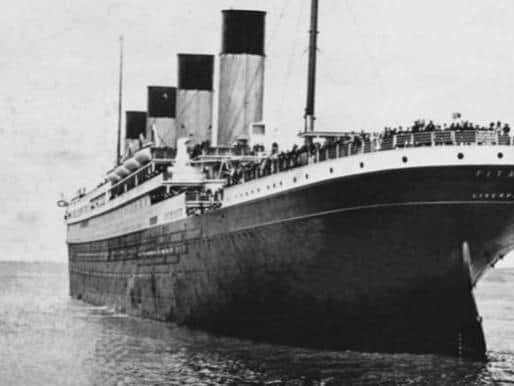

The story of the Sunderland man who survived the Titanic disaster, thanks to a game of cards

and live on Freeview channel 276

One of the very many stories to be told in its aftermath, is that of a glass worker from Sunderland who was one of the lucky survivors.

Had Charles Whilems gone to bed earlier on that fateful night he would never have been heard of again.

Charles’ early life on Wearside

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCharles Whilems was born in Sunderland on March 13, 1881. His parents were Elizabeth and Joseph, who weren’t married until 1885.

According to the 1881 census, held just 21 days after his birth, he lived in 47 Hedley Street in what was then Bishopwearmouth. This is now Millfield, close to where the Lansdowne pub still trades. The street was bulldozed in the early 1970s.

Both parents had been married previously and Charles had at least 13 half-siblings, followed by four full siblings.

By the time he was 19 he had become a glass bender and moved to London. As his Hedley Street home was close to the heart of Sunderland’s historic glass industry, it can be assumed he learned his trade on Wearside.

His £13 ‘trip of a lifetime’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1900 he married a Devon woman called Eliza James in Tower Hamlets, London. They had two daughters, Eileen Victoria (later Mrs Rowland Press, 1901-1983) and Leonie Adeline (later Mrs Marcus Charles Randall, 1909-2000). A son called Charles was born in 1911.

In 1912 he bought a ticket for what he must have thought would be the trip of a lifetime. His destination was Broadway, no less. By this time he was a foreman at Messrs Robinson Kings Glassworks and could afford it.

His second class return ticket (number 244270) cost £13. This equates to around £1,500 in 2021. However, £13 in 1912 was a larger chunk of the UK annual salary than £1,500 is today. He was to visit relatives at 2270 Broadway on New York’s Manhattan island.

On April 10, 1912 he boarded the Titanic in Southampton and intended to take the return trip to England aboard the same ship.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis £13 didn’t buy the 32 year-old much privacy on the ship. In second class, passengers slept two to four berths per cabin. These cabins had a washbasin and a chamber pot (in case of seasickness) and bathrooms were communal.

This would, to say the least, become the least of his concerns.

Disaster at the iceberg

He later described the sinking: “A party of four of us had been smoking and playing cards in the second cabin smoking room when the shock came. There was a man named Fox, a Texas ranchman, one other man, and myself.

“We felt a slight jar and hastened to the deck. Even as we did so, we saw the iceberg, huge and white against the dark blue sea, go whizzing past on the starboard side of the ship, just clear of the stern.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We returned immediately to the smoking room and finished our game of cards. By that time we could hear many voices on deck and again went out to learn what had happened.

“Officers were telling everyone that there was no danger and no reason to worry in the least.”

Clearly the officers were wrong. Some time later he was told to put on his life jacket and went to fetch it. He woke two cabin mates and told them what was going on. They just laughed at him then went back to sleep. Charles never saw them again.

Lifeboat number nine

Back on deck he ended up helping women and children into the insufficient lifeboats, before stepping into boat nine himself with more than 50 other passengers. He later described what happened next in horrific detail.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe said: “We rowed about 400 yards from the ship before we saw her settling slowly by the head. Then there was an explosion. The lights went out and the ship seemed to break, her nose plunging down and her stern bucking almost straight up.

“I put my hands over my ears to shut out the wailing as the lights went out, and those on board began to realise that something dreadful was going to happen. The screams grew fainter and fainter very soon, however.

“Later in the morning, when we were aboard the Carpathia (another passenger liner, built in Wallsend), I saw many of the bodies floating by.”

‘All well saved’

Charles was one of the 710 out of the 3,327 on board to survive the disaster. The telegram, or Marconigram, he managed to send home still exists. It was written in pencil, stamped “Carpathia” and dated April 18; three days after the sinking.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt said: “Mr I Whilems 2270 Bradway (sic) N.Y.C. All well saved. Charles Whilems”.

It is hard to imagine Charles’ state of mind at this point, or how much the trauma affected him later. What we do know is that he returned to England and continued to work as a glass bender. He and Eliza had another daughter, Enid Cecilia (later Mrs William Chapman, 1913-88).

Charles and his family later moved to Ilford in Essex, which is where he died on February 15, 1940 aged 58. His widow Eliza died on March 28, 1941. Little detail can be found about Charles Whilem’s later life, although we do know that he was cremated in Essex.

Nevertheless, this Sunderland man will forever be part of perhaps the most famous/infamous event in all of maritime history.