Sunderland’s role in the rise – and fall – of the slave trade

and live on Freeview channel 276

But it’s not that simple. We still live with the consequences. Whatever your thoughts on the statue toppling of 2020, the topplers were not trying to “erase” history. Quite the opposite. The shame continues.

The western port cities of Bristol, Glasgow and Liverpool have particularly ignoble ties with Britain’s slave trade; and the immense wealth it created at the expense of up to 12 million kidnapped Africans.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut what was Sunderland’s role in this repellent story? Although not considered to be at the forefront of one of history’s greatest embarrassments, one prominent Wearside family made an appalling contribution.

However, it was an adopted Mackem who played a pivotal role in its abolition.

The Hiltons: shameless slave owners

The rich and powerful Hilton family owned Hilton Castle, which had a slight name change to Hylton Castle in the 19th century, and remains a familiar Sunderland landmark. They were seafarers with interests in the Caribbean.

Anthony Hilton acquired a tobacco plantation and became governor of St Kitts in 1625. Other Hiltons settled in America and the Caribbean. They needed more labour, but had no intention of actually paying anybody and so used abducted Africans to serve them.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn the 1740s Ralph Hilton, born in County Durham in 1710, also settled in Jamaica where he and other Hiltons obtained sugar plantations.

Over 5,000 people with the surname Hylton live in Jamaica today. This is hardly a proud Sunderland legacy. The ancestors of most of those people had the surname forced upon them.

A more famous Wearside name is also inextricably tangled with the slave trade. Washington.

George Washington

Five generations of the family lived in Washington Old Hall. John Washington from Sulgrave, Northamptonshire, emigrated to Virginia in 1656. His great-grandson, first US first President, George Washington, was born on his father’s slave plantation there in 1732.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen his father, Augustine Washington, died in 1743, George inherited 316 slaves. This didn’t sit well with George who, it should be remembered, was only 11 at the time.

When Washington died in 1799 his will decreed that all his slaves be freed upon the death of his wife Martha. This was unusual and few other slavers followed his example.

Milbanke and Londonderry

Following British abolition in 1807, the slave trade continued illegally, or within loopholes. British ships regularly flew American flags. Slavery remained legal in the USA until 1865.

One such ship was The Orange Grove, probably built on the River Wear in 1812 and believed to have originally carried fruit, but which became a slave vessel.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1791 Sir Ralph Milbanke became MP for County Durham, which included Sunderland. He lived in Seaham Hall (his daughter Annabella married the poet Byron there in 1815).

Milbanke was a committed abolitionist and, according to what his wife wrote in 1792, he only remained in London to take part in a parliamentary vote against the slave trade. He was a key ally of Wilberforce.

Milbanke died in 1825. Seaham Hall passed into the ownership of Lord Stuart; later Third Marquess of Londonderry.

His half-brother, the Second Marquess better known as Lord Castlereagh, was Foreign Secretary 1812-1822 when he negotiated treaties which restricted the slave trade of Portugal and Spain, and prevented British slave ships from sailing under foreign flags.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut one adopted Mackem, abolitionist and pamphleteer used his experiences to convincingly and decisively argue against slavery; and eventually make it illegal.

James Stanfield: hero and abolitionist

James Field Stanfield, born in Dublin in 1749, became a merchant seaman and his memoirs became hugely instrumental in the repeal of slavery.

On a 1774-1776 voyage on a cargo ship from Liverpool to Benin in north-west Africa, he saw first-hand how captured Africans were shunted onto slave vessels and shipped in horrendous conditions to the West Indies.

To Stanfield the ship was “a floating dungeon” and in 1788 he wrote Observations on a Guinea Voyage, which gave gruesomely graphic descriptions of his voyage.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAn outright lie was circulated (there is nothing new under the sun) that slaves preferred conditions in the West Indies to those in Africa. In fact, those from Benin had been well-fed, organised, civilised and, above all, happy.

Not that white sailors fared well either. Unused to the conditions, most of them died of disease in Benin or in transit across the Atlantic. Stanfield’s pamphlets gave stomach-churning, accurate descriptions of the treatment of both slaves and crew.

One passage told of a sadistic captain having a female slave flogged before him in his cabin for some trivial offence.

The sailor administering the punishment was deemed to be insufficiently enthusiastic about his task. So he too was flayed and the woman flogged again “until her back was full of holes”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdStanfield bandaged the unfortunate woman. The ship’s doctor had died.

His accounts were serialised in British and American newspapers. It took some years for this to have the desired effect, but the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act was eventually passed on March 27, 1807.

A volume of his works was published in 1808 and dedicated to Sir Ralph Milbanke.

His extremely varied CV shows that Stanfield later became an actor and lived in Sunderland for more than 20 years. He was a wine and spirit merchant in High Street East between 1793 and 1796.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

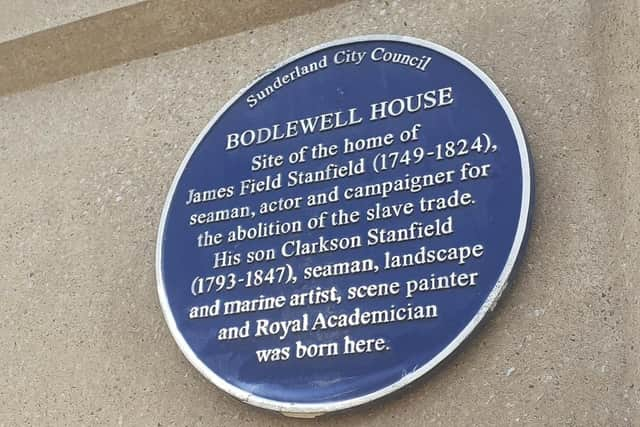

Hide AdA blue plaque in honour of him and his artist son, Clarkson Stanfield (a friend of Charles Dickens), can be seen today on a building opposite the Exchange Building.

The American academic Professor Marcus Rediker, author of The Slave Ship: A Human History, described James Stanfield as “an unrecognised hero of the movement to abolish the slave trade”.

Sunderland has therefore made significant contributions both ways to the story of the slave trade. It would be wise to remember all of it; both noble and deplorable.