'Sunderland led the way to help autistic people' - says city's Birdman flying contest winner

and live on Freeview channel 276

More than half a century on, Paul, now 74, considers himself to be “a very lucky man” to have found his way to a region with a heart big enough to not only transform the quality of life for his own family but countless others too.

“If I hadn’t come here, it could have been so different,” he says, as we chat in a building that was to become Thornhill Park School, one of several pioneering educational centres run by the award-winning North East Autism Society.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Sunderland Echo has joined forces with the society to launch our new joint All To Play For campaign to help fund £25,000 worth of equipment for the school after it moved to its new home in the city’s Plains Farm area earlier this year.

It hopes to repeat the success of our 1980 appeal for the school – an appeal Paul himself played an instrumental part in.

Paul, originally from Sevenoaks, in Kent, never intended staying so long when he applied for a job, teaching pharmacy at far-off Sunderland Technical College, in 1966.

Just married, he and his wife, Christine, planned to give it three years but they discovered, to their surprise, that they liked Wearside.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It was a totally different culture, but it wasn’t pretentious – the people were so down to earth and friendly,” he recalls.

Alarm bells

The couple were overjoyed when their first child, Jamie, was born in October 1970. “You do what all parents do – count their fingers and toes,” recalls Paul. “He was jaundiced but, otherwise, everything seemed OK.”

But as time passed, alarm bells started ringing in Paul’s head.

Jamie was a slow feeder and so quiet that Paul remembers thinking that he was “too good”. The alarm bells got louder shortly afterwards when he was listening to a radio programme about autism, and a mother used the same

phrase about her baby: “He was too good.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBy the time Jamie was two, Paul and Christine had grown increasingly anxious, realising that Jamie wasn’t hitting the usual developmental markers.

What is autism? Your questions answered

He could understand instructions but had to do things slowly, and he struggled with communication.

Over the next two years, his development and speech seemed to improve, and the family was complete when a little sister, called Rachel, was born.

However, things went downhill when Jamie was taken to hospital after an accident at home.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhile he was there, he picked up a terrible gastro-enteritis infection, and there were fears he wouldn’t pull through.

“He survived but we felt he was never the same after that,” remembers Paul.

“He gradually lost his words and started giggling a lot. He also did strange things, like randomly adding the word ‘polo’ to the end of his sentences.”

Jamie also suffered from depression and had trouble sleeping. He began engaging in routines, such as repeatedly opening the door of his toy bus.

Specialist assessment

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe couple knew something was wrong so Jamie was taken for an assessment by a child psychiatrist who delivered a “shattering” verdict: “I think he’s autistic.”

Jamie was to become the youngest person in the north of England to be formally diagnosed with autism when the condition was confirmed on May 31, 1975.

“They were still working out what autism was in those days,” says Paul.

“Despite his other problems, he was sociable and had good eye contact, we couldn’t believe what we were being told after the initial assessment.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We walked home without speaking, then looked at each other and said ‘what the hell are we going to do now?’”

Paul had become a regular reader of the local paper and he recalled an article a month earlier about someone who was trying to start a school for autistic children.

He searched through back issues, discovered that the man was called Norman Howe, and managed to track him down.

Norman invited Paul to a hotel in Jesmond for the annual general meeting of a new organisation called the Tyneside Society for Autistic Children.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I learned a harsh lesson by agreeing to go because I ended up being made secretary!” says Paul.

Ignorance about autism was rife at the time. The Labour MP for Sunderland North, Fred Willey, asked a question in the House of Commons about how many autistic children there were in the North of England.

The nonsensical answer given was 19. When an eminent child psychiatrist was asked why there might be such a relatively low figure, the unbelievable response was that autism was associated with intelligence – and the North East wasn’t known for its intellectual prowess.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Tyneside Society for Autistic Children was made up of a passionate band of about 20 parents and a few professionals.

The president was a renowned child psychiatrist, Professor Israel (Izzy) Kolvin, who had written seminal papers establishing the difference between autism and schizophrenia.

Campaign launch

To launch a school, the society needed a building. A derelict, former Jewish school, at Number 21 Thornhill Park in Sunderland, was identified but £25,000 had to be raised to buy it.

There were even times when Paul, along with other committee members, had to use their own homes as potential security against loans.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“In those days, that was a lot of money, but we did all sorts of things to fundraise and, crucially, we worked hard to get the media on board,” says Paul.

The importance of good local papers, embedded in their communities, was underlined by the “fantastic” support given by the Sunderland Echo and local radio stations.

“The local media was hugely important – they were the first people we needed to get on side and they did us proud,” says Paul.

The media interest helped to unleash the most extraordinary response from the local community.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJust about every workingmen’s club in Sunderland staged an event: darts, snooker, dominoes, talent contests, you name it.

The Houghton-le-Spring Pigeon Fanciers Association homed in with a £500 contribution, leek clubs did their bit, along with schools and churches.

“Punk was big at the time and you’d be amazed how many punk rockers shoved money in collecting tins,” says Paul.

Sunderland Football Club played a starring role.

Year after year, a fundraising dinner was staged at Ramside Hall Hotel, in Durham, to celebrate the 1973 FA Cup win and legends from that team, including Jimmy Montgomery, Bobby Kerr and Dick Malone, have remained in touch.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe city was also a national hotbed for basketball at the time and Sunderland Basketball Club was another ally, staging events that included a pie-eating competition.

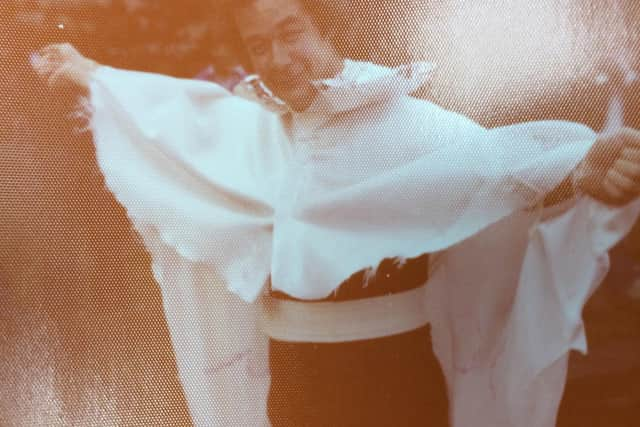

There was even an infamous “Birdman” contest, with 13 college students trying to “fly” across the River Wear in home-made contraptions.

Paul joined them in a fibre-glass Flying Squirrel costume – and emerged triumphant.

“I had visions of myself gliding across the water, but I flew like a shovel. Luckily, the others were even worse,” he chuckles.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“When I landed, it was freezing cold and I got a mouthful of sewage and seawater - but it was worth it to win.”

Slightly less intrepid, but just as valuable, were Paul’s contributions on the public speaking circuit, spreading the word wherever he could. “I suppose I was a bit gobby, and I was good at dealing with hecklers in the clubs, so people listened,” is how he humbly puts it.

All To Play For: How our £25,000 appeal will help autistic pupils

It all added up to a strong community voice and, in the end, around £80,000 was raised, with the biggest donation of £12,000 coming from the National Autistic Society.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNumber 21 was purchased and rebranded as Thornhill Park School, while the remaining funds were banked for staff recruitment and restoration work, with tradesmen volunteering their services for free.

It was hard work, with all kinds of challenges to overcome. The boiler flooded, tree roots got in the way, but the building eventually became fit for purpose.

“People kept telling us we’d never get it off the ground, and there were times when we felt like giving up, but we stuck with it and, slowly but surely, we got there,” recalls Paul.

Despite the progress that had been made, there was still a fundamental problem: local authorities weren’t sending children to the Society because they weren’t convinced it was a credible option.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThat credibility gap was filled with the appointment of Sheela Ramm as headteacher.

Mrs Ramm had been teaching autistic people in Croydon and was prepared to accept the daunting but exciting new challenge of managing this new school up in the North East.

“Her appointment was absolutely crucial, and she made so much happen,” says Paul.

“She moved into the empty school with her three children until it got sorted and went beyond the call of duty in so many ways. She took a huge risk.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMore staff were recruited and Paul found himself left with sorting out the salaries.

“I’m dangerous with money but someone had to do it,” he sighs. “Thankfully, staff from the wages department at Sunderland Polytechnic came to the rescue and volunteered to take it on.”

Still, there were no pupils to teach, but it all changed when a telephone call echoed through the empty building.

Turning tide

It was Essex Social Services – blissfully unaware that the school didn’t have any pupils – with a question: “Can you take another one?”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We could probably squeeze one in,” was the excited reply and, suddenly, Thornhill Park School had its first pupil – a 13-year-old girl called Jane. A second call came in soon afterwards from Clitheroe Education Service, seeking another placement, then a third request for support was made from Nottingham.

The momentum continued, with social services in Sunderland sending children to the new specialist school on their doorstep.

By the end of the year, Thornhill Park – the first residential school for autistic children to be open all year round – had a full cohort of 12 pupils.

The 12th pupil was Paul’s son, Jamie.

Then aged 12, he had been cared for in a residential school in Scotland, but that placement was coming to an end, and having him back in his hometown meant the world to Paul and Christine.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Jamie was one of the more challenging pupils, but we were able see a lot more of him and take him on days out. It made a massive difference,” says Paul.

An opportunity then arose to acquire the former Carley Lodge infants’ school from Sunderland City Council for a peppercorn rent. That was used for children aged five to 11 while the older ones stayed at Thornhill Park.

By 1992, with referrals continuing to grow, the society needed to widen its horizons, and Paul set his heart on an empty building just down the road from Number 21.

It had been “The Hearing Clinic” where Paul had taken Jamie for tests and seemed perfect for the expansion.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWith a deal agreed the name of Thornhill Park School was transferred to the newly acquired site, and Number 21 became freed up as an adult residential centre. Jamie stayed there until he was 17, when Sunderland City Council paid for him to go into adult services care.

Name change

The charity’s name had been amended to the Tyne and Wear Autistic Society but, with the society having an increasing impact across the whole region, it was renamed the North East Autism Society (NEAS) in 2009.

A decade down the line, it continues to go from strength to strength.

“It has grown into a stunning organisation, with dedicated, caring staff doing the most incredible work,” says Paul. “We took it as far as we could, but NEAS has moved it on to a different level altogether and, with more people coming through the system, the need is greater than ever.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJamie is 49 now and has lived in recent years on a farm in Ireland although Paul hopes he will be able to return closer to home soon.

With the experience he gained in the North-East, Paul went on to travel internationally as President of the World Autism Organisation and remains on the committee.

All To Play For: Mum of girl told she would never talk or read backs appeal

Offering his support for our new campaign, he insists: “There’s no doubt in my mind that the UK is the best country in the world when it comes to supporting autistic people - and Sunderland led the way.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“There was nothing in place for families like ours, so parents had to take up the baton. We had to do it for ourselves because there was no alternative. I’m not blaming anyone – it’s just that they just didn’t understand at the time.

“And I don’t claim any righteousness because the devil would do it for his own children, wouldn’t he? We did it for our own children and it just took off.

“I really do count myself as a lucky man to have come to Sunderland because everything we needed was here: low property costs, access to grants because it was designated as a development area, a willing labour force, a great local paper, and, above all, a sense of community that I hadn’t seen anywhere else.

So proud of Sunderland

“I’m just so proud of what Sunderland did; the way they rallied round. They might not have had much but they gave what they could afford. Thank God I didn’t stay in Kent.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I look back and shudder at the thought of everything that happened, and ask myself ‘Did we really do all that?’”

The answer is “yes”. That brave, passionate, determined band of parents – wonderfully supported by the big-hearted people of Sunderland – really did do all that.

And the lives of countless families have been transformed as a result.

*Cheques can be made out to the North East Autism Society and addressed to The Fundraising Team, All To Play For Appeal, Thornhill Park School, Portland Road, Sunderland, Tyne/Wear, SR3 1SS.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOnline donations can be made via the society’s website at www.ne-as.org.uk/appeal/all-to-play-for.

Registration for the Walk for Autism Acceptance can be made by logging to www.ne-as.org.uk/Event/walk-for-autism2020.

Further information is also available by contacting NEAS on (0191) 4109974.