The day they tested Sunderland's Queen Alexandra Bridge by putting eight locomotives on its roof

If you wanted to test a bridge’s ability to hold weight, you would get huge groups of men - or locomotives - to stand on top of it.

Norman Kirtlan, from the Sunderland Antiquarian Society, found out more about the nerve-wracking trend.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPicture the scene that was acted out in Sunderland a hundred years ago.

Eight locomotive drivers were being briefed for their death-defying trip, and what a trip it was.

They were told they were going all the way to the Queen Alexandra Bridge and back.

If it held, it was a sign that the bridge could pretty much hold anything.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne by one the heavy locos steamed onto the roof of the bridge, testing the huge structure and its capacity for carrying traffic safely from one side of the Wear to the other.

Although the railway lines and locomotives have long since disappeared from its roof – the last goods train crossed over in 1921 - the Queen Alexandra Bridge has served the city well for a over a century.

Of course, the test-pilot train driver’s episode took place in the good old days before Health and Safety and Workers Rights.

But if you think that little fiasco was risky, let’s go back another hundred years to the opening of that other wondrous structure – Robert Stephenson’s magnificent bridge over the Wear.

In July 1796, 1,000 volunteers were needed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTheir job was to test the magnificent hump-backed marvel that spanned our glistening river, a hundred feet below.

But the term volunteer was loosely used. The men who stood on top of a bridge were local troops.

Norman added: “Imagine standing there yawning in the morning fret before setting off up the High Street on a little march – you and nine hundred and ninety nine other brave dragoons.

“They stood for an hour in the early morning sunshine, watched over by brave officials and engineers.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThankfully the bridge held, and Sunderland’s new structure, a “bridge with no parallel”, became the envy of the world.

But it was not all good news for the city and the people who used the bridge.

In those days, a toll was imposed for crossing the bridge.

But it did not go down well with the locals. It much hated by Wearsiders, and often abused, sometimes in ways which could almost raise a smile.

One chimney sweep objected so much to paying the halfpenny toll for him and his “climbing boy” that he devised a cunning plan.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOur man was always in possession of a large soot sack, and it was here that the youngster was unceremoniously stuffed and thrown across the master’s shoulders as the grumpy sweep threw his halfpenny at the toll master and trundled across the bridge.

The toll master eventually became suspicious and decided to do a little spot-check, whacking the soot sack with his walking stick. The youngster screams certainly let the cat out of the bag, and our man ended up paying a hefty fine for his troubles.

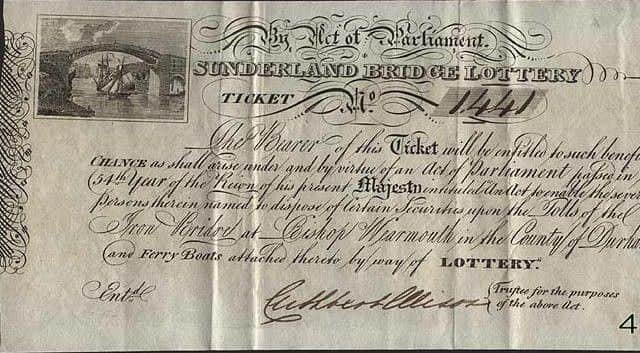

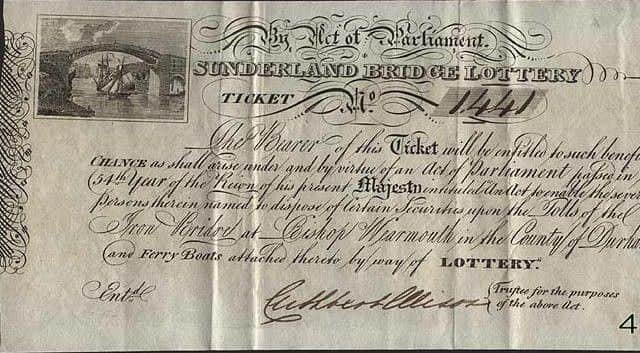

Before the tolls were finally abolished in 1846, lucky Wearsiders could win free passage in the town’s big draw. It wasn’t exactly a high tech affair, but it certainly created a lot of interest and a big splash in the Sunderland Daily Echo.

Once again, when the town had something to celebrate it did it in big style with no expenses spared.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen the tolls were finally abolished, the Mayor in full regalia, paid the final symbolic four penny piece and the town’s workers had a half days holiday!

I must look back to that day in 1956 when my dad’s Standard Eight spluttered to a steaming halt in the middle of the Queen Alexandra Bridge, and I, just a terrified toddler, hung on white-knuckled while four brawny Doxford’s lads pushed us back to terra firma and the relative safety of Clockwell Street.