The priceless Lindisfarne Gospels: Stolen from the North East by Henry VIII and never returned

and live on Freeview channel 276

The manuscript’s recent stint in Newcastle’s Laing Gallery was the fifth time since 1987 it has been displayed in the region. Its previous visit, to Durham University in 2013, attracted almost 100,000 visitors.

The gospels are preserved, with extreme meticulousness, at the British Library (BL) in London. But why are they there? What are they?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHere is a brief history of the 1,300 year-old gospels, described by the BL as “the most spectacular manuscript to survive from Anglo-Saxon England”. To make a rare justifiable use of the description, this is a bona fide national treasure.

The book

In the late 7th century (if this was a film your screen would now go wobbly) a monk called Eadfrith was living on Lindisfarne, aka Holy Island.

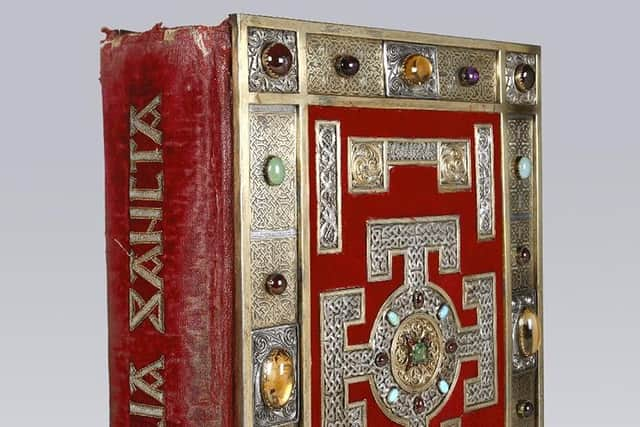

He got cracking on the gospels and can’t have lifted his head much thereafter. Eadfrith is generally given most credit for their creation. If this is correct, then he was an artistic genius, although two other monks are credited with the casing and binding of metal and jewels.

Eadfrith became Bishop of Lindisfarne in around 698 and died in 721. He is venerated as a saint in the Catholic church, yet the gospels are his greatest legacy.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe adjective “painstaking” seems inadequate. Seven centuries before the printing press, with the opening of the first Prontaprint even further away, extreme devotion and sublime talent are behind the Lindisfarne Gospels.

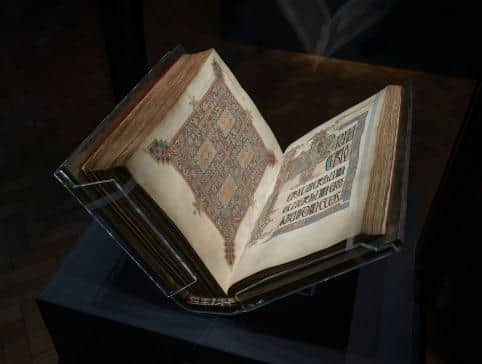

It contains 516 vellum pages, or 258 leaves. Every one is a masterpiece. The text is stunning, yet it’s the artwork which really delivers that (genuine) national treasure status.

Eadfrith never quite completed the book, so a priest called Aldred put additions in the back including a colophon (scribe’s note) in the tenth century.

The manuscript includes five highly elaborate “carpet pages”, so-called because of their resemblance to, well, carpets.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne carpet page appears at the beginning of each gospel from Matthew, Mark, Luke and John; all written in Latin. The fifth precedes the book’s prefatory material. A different type of cross was drawn for each evangelist, but nothing in the book is there merely because Eadfrith thought it looked eye-catching. There is a reason for everything appearing as it does.

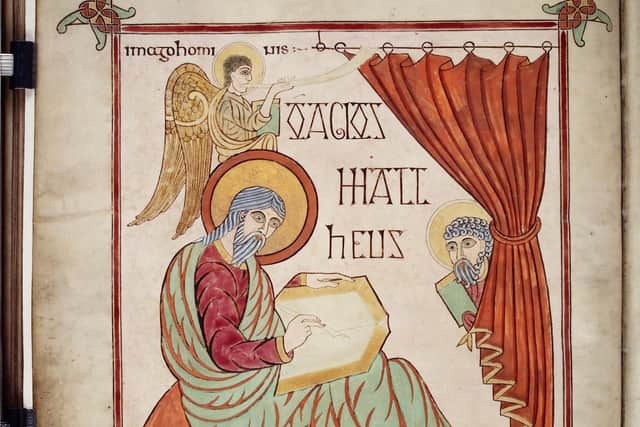

There are also full-page images of the four evangelists. It is a monumental achievement and a feast for the eyes of any Christian. Or Jew, Muslim, Hindu, Sikh, atheist…

Vikings and other scallywags

The Vikings, serial rotters of the misnamed Dark Ages, raided Lindisfarne in 793, but the manuscript survived. The monks left the island in 875, taking the book and other treasures with them.

The monks eventually settled in Chester-le-Street, as did the sacred book. Post-1066 the Normans showed their respect for religious history by leaving the book in Durham.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut in 1539 along came psychotic Tudor fatty Henry VIII and his appalling Dissolution of the Monasteries; a sort of nationalisation programme, but with extreme violence. It was a deranged overreaction to corruption in the Catholic Church; and hugely profitable.

The pustulant tyrant ordered the destruction of St Cuthbert’s tomb; and theft of the Lindisfarne Gospels. The now knock-off book was later sold to the loaded Sir Henry Cotton.

His grandson, Sir Robert Cotton, died in 1631 and bequeathed the manuscript to the nation; a step in the right direction, although the issue of it not really being Cotton’s property to bequeath is rarely touched upon.

The British Museum took charge of it in 1753. The British Library was founded in 1973 and there it is preserved today.

Why is it still in London?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe British Library recently gave this newspaper a courteous response to this question. It seems that Northumbrians could be easily persuaded to battle the Vikings, William the Conqueror and Henry VIII, but can’t fight the British Library Act 1972.

The BL told us it “has a statutory obligation to ensure the long-term preservation of the Lindisfarne Gospels”.

It added: “Our St Pancras site was purpose built for the nation to accommodate manuscripts of such significance and the library has one of the most experienced curatorial and conservation teams in the world.

“The library follows a conservation programme recommended by an international committee of leading conservators and curatorial experts, whilst trying to provide access to the widest audience possible, today and in the future.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“When on display in the Library’s free Sir John Ritblat Gallery: Treasures of the British Library, we turn a page every three months to limit the amount of light and physical stress on any one opening.

“The volume is rested from display for six months after eighteen months display. We have also digitised the manuscript so it is freely available for everyone online at www.bl.uk/manuscripts.”

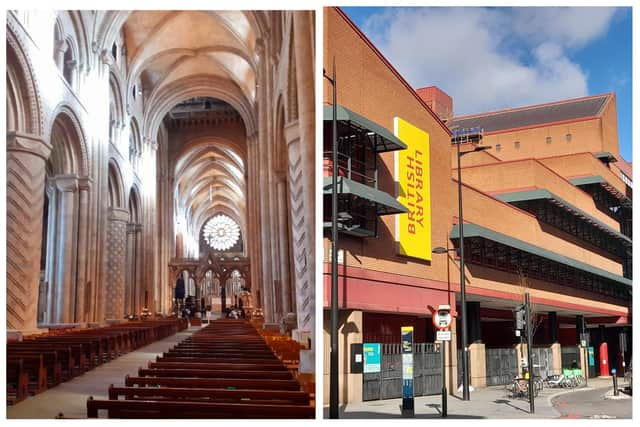

The BL takes excellent care of the book. But this expertise can be shared. If necessary. The Palace Green Library in Durham, for example, where it was displayed in 2013, has experts of its own.

The book was created to honour Cuthbert, Eadfrith’s hero and the patron saint of Northumbria, which is roughly the area between Hull and Berwick. So why keep it in London? The peril awaiting it, should it return home, is not abundantly obvious.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

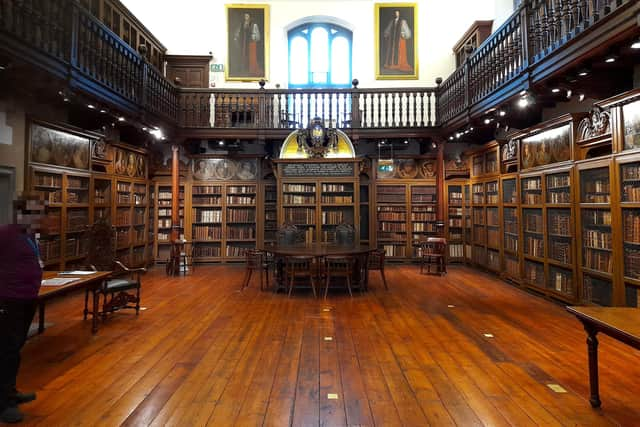

Hide AdThen there is the setting. It deserves better. The (arguably) most suitable home, security being a consideration, would be Durham Cathedral; one of the most aesthetically beautiful and historically important buildings in Europe.

The dowdy red-brick British Library on London’s Euston Road is functional, but has little to offer either aesthetically or historically. In fact it bears a more than passing resemblance to an unusually large branch of Wilko.

Furthermore, no argument the BL posits will persuade those who feel the book has been stolen property since 1539. The Government could do right, the rejection of a 2021 parliamentary petition notwithstanding.

So please return the Lindisfarne Gospels to where it was intended to be.